WARNING: This story contains graphic details that may disturb some readers.

Russell Colwell has spent most of his existence in prison, nearly 37 years and counting. Measured in days, that’s more than 13,000. His victims — the many people who loved Patrizia Mastroianni, and were forced to suddenly live without her — have served a parallel sentence, equal in time but infinitely worse.

“On Oct. 14, 1987, life stopped,” said Carmela Roznik, Mastroianni’s older sister, speaking at a recent Parole Board hearing. “We were never whole again, no longer to live an ordinary life.”

How could they? How could anyone? It was an unthinkable crime, as random as it was brutal: an innocent 14-year-old girl from Sault Ste. Marie attacked and stabbed to death inside a Korah Collegiate bathroom, targeted by a sexual predator stalking his former high school.

“My sister’s murder continues to haunt me,” Roznik told the Parole Board, the killer seated just a few meters away. “‘If only, if only’ were words stored in my memory…Having seen pictures of the crime scene at court proceedings, I am unable to forget the image of my sister’s body lying lifeless in the washroom.”

“I ask myself: ‘How can a man who commits such a crime ever be considered to let free?’” she continued. “Our family are the ones who deserve the freedom of peace of mind knowing that Russell will remain in jail for his entire life.”

Sadly, they can’t cling to even that. All these decades later, the man responsible for one of the city’s most notorious crimes is determined to see the outside of prison — and with every attempt, the 56-year-old appears to be getting closer.

As SooToday reported earlier this year, Colwell’s latest move was to ask the Parole Board of Canada to grant him an escorted temporary absence (ETA), a short-term supervised release typically approved for medical appointments, community service or “rehabilitative purposes.” Although that request was denied after a hearing on March 28 — the same one where Roznik spoke so passionately about her little sister — Colwell promptly filed an appeal, which is now under review.

“I think we’ve realized that this is just the beginning of a new fight,” says Tiziana Palumbo, Mastroianni’s younger sister, who also attended the latest hearing. “It wasn’t a relief that he was denied. It was more like: This is our reality. It’s getting closer to him being released and the frequency of these hearings is going to be much more often, so we’re just preparing for that.”

Roznik and Palumbo are both very private people. Although their sister’s horrific murder made national headlines at the time — and has never been forgotten around here — they do their best to avoid the spotlight. They only agreed to speak to SooToday, and to share Roznik’s full statement to the Parole Board, because the community has been so supportive and they want people to know what’s happening.

“We want to raise awareness of what the process is because it was an eye opener for us,” Palumbo says. “It really opened our eyes to what the privileges are for an offender.”

“The system is broken,” Roznik adds. “If people think he’s behind bars in a little cell, he’s not.”

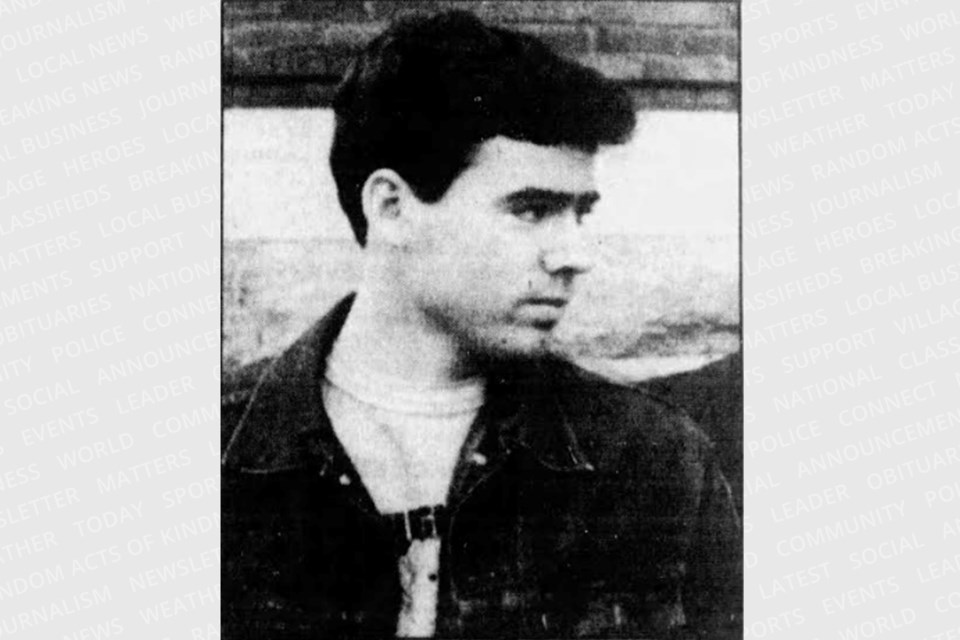

Colwell was 19 when he walked into Korah Collegiate that autumn Wednesday in 1987, fixated on sexual assault. Ironically enough, he was a first-year law and security student at Lake Superior State University. After spotting Mastroianni, he followed the curly-haired Grade 9 into a cubicle and stabbed her multiple times. Police later found semen on her 14-year-old body.

Roznik was 17 back in 1987, Palumbo just 11. It was a much different time, a world without smartphones or Google or school lockdowns. Brian Mulroney was prime minister and U2 had just released their landmark album The Joshua Tree. No one yet knew the names Paul Bernardo or Karla Homolka.

“Russell walked into our lives and destroyed us all,” Roznik, now 54, told the Parole Board. “We had to watch our parents do what no parents should ever have to do: they buried a daughter at the prime of her life. The sense of loss was so unbearable, my parents were never the same — forever changed.”

Colwell was ultimately convicted of first-degree murder and sentenced to life in prison with no chance of parole for 25 years. But for Mastroianni’s shattered family, the end of the criminal trial was just the start of their life sentence.

In her lengthy statement to the Parole Board, Roznik laid out — in heartbreaking detail — the immeasurable damage Colwell left behind. Her devastated mother would often stare at Patrizia’s photo in the living room, “longing for a child who was never coming back.” Her dad blamed himself “for not being there to protect” the daughter he adored. The children? “We found ourselves feeling like orphans, having to fend for ourselves,” Roznik said. “We now had to be the rock and pillar of a broken family.”

All sense of joy, any semblance of peace, was ripped from their home. “We no longer participated in celebrations with family, friends or neighbours because we were ashamed of laughing, and the display of the happiness of others was like a stab wound to the heart,” Roznik said. “Thirty-six years later, my heart still aches when I see her childhood friends. Countless missed memories and opportunities that were snatched from Patrizia’s life.”

For more than two decades, there was one thing that gave the family a tiny bit of comfort: the knowledge that Colwell would be locked in prison for a very long time, unable to harm anyone else. That’s not true anymore. Approaching his 37th anniversary in prison, Colwell has ramped up his efforts to finally get out — forcing Mastroianni’s loved ones to muster up the fight to try to keep him there.

“We are given no option to do anything different,” says Palumbo, now 48. “This is what we have to do. It’s horrifying to think that he can be released because the risk level in our eyes is so very high.”

Previous rulings released by the Parole Board provide a small window into Colwell’s decades behind bars. In the late-1990s, for example, he was placed in segregation for repeatedly exposing himself to female employees. In 2010, he lost his job as a cleaner at a medium-security prison after locking himself in a women’s washroom and refusing to respond to staff. Two years later, his case management team, including psychology staff, reported that he was “engaged in intense/problematic ruminations and preoccupations related to sexual offending.”

The role of the Parole Board, simply put, is to weigh two scenarios: Would releasing the offender present an “undue risk to society,” or would it contribute to the ultimate goal of protecting society by facilitating the inmate’s reintegration “as a law-abiding citizen”?

Colwell’s first attempt at day parole, filed in 2014, was denied because the board felt he still posed an undue risk. Seven years later, in November 2021, the board refused his application for full parole, once again citing the continued danger he presents.

“You planned to sexually assault a female and loitered around your old high school waiting for an opportunity,” the board wrote in that 2021 decision, describing Mastroianni as “an innocent person in the wrong place at the wrong time.”

Despite the board’s denial, the ruling did lay out a potential path for Colwell’s eventual parole. It noted the results of a recidivism assessment, which indicated that “four out of five offenders with a similar score will not commit an indictable offence within three years of release.” The Correctional Service of Canada (CSC) also assessed his accountability and motivation level as “high” and his reintegration potential as “medium.”

At the time, Colwell was imprisoned at an undisclosed medium-security facility. A psychologist noted that the “next logical step” would be a transfer to minimum security, followed by what the CSC described as “a gradual reintegration” into society that would include “a sustained and successful period of day parole.”

The first part is now complete; Colwell was transferred last year to an undisclosed minimum-security prison in southern Ontario. As for the next step — “gradual reintegration” — Mastroianni’s family received letters in the mail in November 2023, informing them of Colwell’s application for a temporary escorted absence.

“I was so angry,” Palumbo said. “It was another re-victimization. It’s ridiculous that we have to rearrange our lives to travel there for the hearing. Basically, we have to go and fight for our sister because they’re running out of room and he’s done his time — so what else?”

As SooToday reported in January, the family went public with a request, asking community members to write to the Parole Board about how this long-ago crime impacted their lives. More than 100 people answered the call — but by law, the family isn’t allowed to see any of those letters. Only Colwell can read them.

Until the day of the hearing, Roznik and Palumbo also weren’t privy to the actual reasons for Colwell’s request for a temporary escorted absence. Only after arriving on March 28 did they learn that he wants to spend a day doing landscaping work outside a federal building — a building that is located near a university and an elementary school. The sisters were stunned.

“His crime was very opportunistic, and now he’s chosen a site where there’s going to be an opportunity,” Palumbo says.

“That’s his fantasy,” Roznik adds.

But nothing shocked them more than the scene they encountered at the minimum-security prison where he’s housed.

“We got an email indicating that offenders may be present at the front gates when we arrive, so we were obviously heightened because of that,” Palumbo says. “And when we pulled up, we saw it was completely open concept. We had to walk through the parking lot and into the building, and there were offenders all over the place identified with blue shirts, cleaning the yard or mopping the floors.”

They soon discovered that Colwell now lives alone in his own apartment-style unit, free to cook meals and visit fellow inmates. He wasn’t brought to the hearing room in handcuffs or flanked by guards. Wearing a blue dress shirt, Colwell looked more like an employee arriving at the office than a convicted schoolgirl killer.

“Basically, we look at it as though he’s already free,” Roznik says.

The hearing began with Roznik’s prepared statement. As she spoke, she says, Colwell wiped his eyes with a tissue — “pretending like he was crying.”

“Our sister was murdered in a very barbaric, indescribable and inexcusable manner,” Roznik told the board members. “As she was taking her last breath, he continued to violate her in pursuit of his own depraved sexual gratification. No human being deserves such a death.”

SooToday did not attend the hearing on March 28, and the Parole Board did not release a written decision. But Roznik and Palumbo say the two board members peppered Colwell with tough questions, poking holes in his plan. Why would you choose a location so close to a university? What if you’re triggered by something you see or hear? What will the level of supervision be?

The board members also made a point of acknowledging the dozens of emails they received from people back in the Sault. There were so many arriving every day that an employee had to be assigned to process them all.

“We really did feel the support of the community the whole time, and we want people to know that,” Palumbo says. “It was definitely helping us get through this, and it really made a huge impact on the Parole Board knowing that: yes, this many years later, this crime is still impacting people.”

In fact, Palumbo says some of the letter writers should consider registering with the Parole Board as victims. Perhaps they were a close friend of Mastroianni’s, or a teacher working at the high school that day.

“They can get the support and resources they need, which is a really important piece,” Palumbo says. “The other benefit of being a registered victim is you are able to stand at these hearings and read your own statement. The more we are, the louder we are.”

When the hearing finished, the two board members briefly deliberated before sharing their decision.

“She said: ‘We want you to know that you’ve been denied, not because of your own rehabilitation, but because of the location of your plan,” Palumbo says. “His plan was really weak and they made that clear, but he has kind of checked all the other boxes.”

The whole process didn’t take very long. They arrived at the facility around 8 a.m. and were finished before noon. As they drove away, their emotions were mixed: relief that he wasn’t getting out just yet, but fully aware he eventually will.

“He’s going to persist,” Palumbo says. “He is going to 100 per cent keep applying.”

They were right. On May 28 — exactly two months after Colwell’s application was denied — the sisters were sent another letter in the mail, informing them of Colwell’s request to have the Parole Board’s Appeal Division weigh in.

“The Appeal Division reviews the decision-making process to confirm that it was fair and that the procedural safeguards were respected,” the letter reads. “The Appeal Division has jurisdiction to re-assess the offender’s risk to reoffend and to substitute its discretion for that of the original decision makers.”

Three months later, the family has yet to hear the result. Whatever it is, they know their fight isn’t over. Not even close.

“This is our life sentence,” Roznik says.