I was reminded of Earthquakes the other day and I thought a story was in order. Some of us in Northern Ontario live in an earthquake zone while others work underground where the ground is always moving.

As the day the year 2000 dawned, I recall the Earth's crust sent out a rattling reminder to Ontario residents. At 6:22 a.m. on Jan. 1, an earthquake with a magnitude of 5.2 radiated out from an epicentre 70 kilometres north of North Bay.

The strongest tremor to hit Ontario in 65 years was felt as far east as Ottawa, as far west as Owen Sound, and as far south as upstate New York.

My mother remembered the Halloween eve of Nov. 1, 1935, an earthquake took place approximately 10 km east of Témiscaming, Québec.

This earthquake was felt west to Fort William (Thunder Bay), east to the Bay of Fundy and south to Kentucky and Virginia. She said chimneys in North Bay fell over or were damaged and cracks developed in the homes having solid brick walls.

Mark Hall sent me the story idea.

He is a geologist living within the City of Greater Sudbury and he is a “professional landman,” - an industry term not so familiar to the general public. Promised Land is the 2012 movie drama about one particular landman played by Matt Damon with a storyline highlighting the environmental issue of fracking.

Hall specializes in hard rock property acquisitions, mineral prospects and project development. He has more than 20 years of experience in acquiring and managing mineral lands, for both the government and private companies in Canada and the USA.

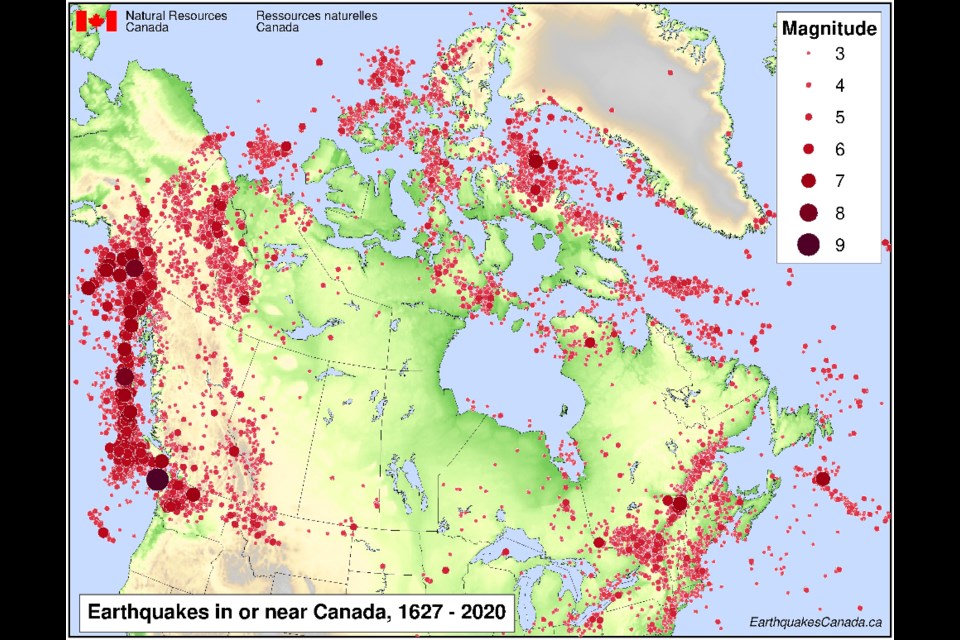

He sent along a map of Ontario showing where earthquakes are most frequent.

Earthquake Primer

So a challenge emerged to find out more.

Dr. Allison Bent of the National Earthquake Hazards Program, Natural Resources Canada said Ottawa and Mattawa are in what we generally refer to as the Western Quebec Seismic Zone; it is a broad zone of moderate earthquake activity that extends roughly from Montreal to Ottawa and from northern New York State to the Timiskaming region; within the seismic zone, there are several earthquakes of magnitude two or higher every month and a few larger than magnitude three every year.

“From time to time, there are larger earthquakes. The one most people tend to remember is the magnitude 5.0 earthquake that occurred near Val-des-Bois on 23 June 2010," Bent said. "The largest earthquake in this region that we know about occurred in 1935 - magnitude 6.1 near the Town of Témiscaming.”

My mother was right.

Bent said you can create a customized search (either rectangular or circular area) of the Government of Canada Earthquake Database if you are looking for a more specific region. (Please, remember to use negative numbers for degrees West).

“The Ottawa River is a reactivated ancient rift (fault) structure. At one time it was believed that it was the cause of most of the earthquakes in the region but that is no longer the case," she said. "Some earthquakes may be related to it but most occur further east. Because the earthquakes in this region have been too small to rupture the surface of the earth, it is difficult for us to pinpoint on which fault(s) the earthquakes are occurring. There are many mapped faults but not all of them are active. “

The hazard maps, (see photos) represent the probability of shaking exceeding a certain value over a specific period of time.

“They are somewhat analogous to weather forecasts in that they are probabilistic. However, weather forecasts deal with probabilities over a short time period (50 per cent chance of rain tomorrow) and earthquake hazard assessments concern longer time periods (2 per cent in 50 years is the standard). Two per cent in 50 years might not be very helpful if you are worried about whether there will be a large earthquake tomorrow (we can’t answer that) but it is when you are constructing a building you hope will last for a century," said Bent.

"Earthquake engineers take the hazard values provided by seismologists and use them to make recommendations to enable buildings to withstand the expected shaking. The hazard maps are updated periodically as our knowledge increases. The earliest ones were quite simple and just defined hazards as high, moderate or low," she explained.

"We now produce a suite of hazard maps for different frequencies and other ground motion parameters as some buildings are more susceptible to shaking at high frequencies (single-family houses) and some to longer periods (highrises) and provide more precise measures of shaking.

"The simplified maps are found here. For context, these are useful in comparing the relative hazard at different locations and are based on the 0.2 sec period map, which reflects the frequency most likely to affect 1-2 storey buildings.

“Globally earthquakes are one of the most expensive natural disasters; worldwide and within Canada, some regions are far more susceptible to earthquakes than others and this can be seen in the simplified seismic hazard maps; some of the areas with high hazard have low populations densities and little infrastructure (offshore Arctic Islands) and some are heavily populated (Vancouver Island, BC lower mainland); earthquakes aren’t really a concern in the prairies- that’s not to say they can’t occur just that damaging earthquakes are unlikely; areas of moderate hazard, such as the Ottawa area, aren’t expecting anything the size of the 'big one' talked about for the west but can experience earthquakes large enough to cause damage.

"How much damage an earthquake causes is related to many factors, among which are the magnitude of an earthquake, how far away it is, building and infrastructure, construction, and soil conditions (hard rock vs. soft soil).

"Devastating earthquakes are rare occurrences. Damaging earthquakes happen more often but don’t necessarily cause buildings to collapse- broken windows and chimneys, small cracks, or damage to the contents of buildings are more common.

"Most earthquakes, including many large ones, do not cause damage.

"People who live in seismically active areas should be aware of it and know how to protect themselves and their families. Find resources here but also be aware of other local hazards, which may be of greater or lesser concern depending on the region and the person’s individual tolerance for risk.”

Mines and Earthquakes

But the ground underneath moves in other ways, especially in the mining sector so important to society and Northern Ontario. “If it is not mined, it’s grown and if it is not grown, it’s mined,” is an adage commonly spoken of Northern Ontario. The Canadian Ecology Centre’s also offers free mining teachers tours - something to think about.

I ended up learning a great deal about all of this as it applies to earth movement and mining from Marty Hudyma, Ph.D., PEng., Associate Professor -Mining Engineering Program, Bharti School of Engineering, Laurentian University. He explains complex topics in layperson terms, a teaching skill in itself.

First off there is a great deal of scheduled blasting in mines which creates seismic activity, he said.

“There are 11 active underground mines in the Sudbury area at the moment. Nine of the 11 mines have seismic monitoring systems and are recording seismic events daily. There are about 25 underground mines in Ontario, with about 75 per cent of them recording seismic events daily. Almost all of these mines are operating at a depth in excess of 1000 metres,” Hudyma said.

The following is important to grasp so back to high school we go.

“In mines, the most widely used measure of event size is magnitude. Magnitude is a logarithmic scale. Each step up the scale is a 10 times increase in event size. So a magnitude +3 event is 10 times bigger than a magnitude +2 event, and a magnitude +3 event is 100 times bigger than a magnitude +1 event," Hudyma said. "Because magnitude is a logarithmic scale, magnitudes can be smaller than 0 (zero). Events smaller than magnitude 0 are termed microseismic. Events bigger than magnitude 0 are termed macroseismic.

"More than 99 per cent of the events recorded in mines are microseismic (smaller than magnitude 0). Microseismic events rarely cause any visible rock mass damage to mine excavations.

"Most seismically active mines record more than 100 events per day. Microseismic seismic events are a normal rock mass response to deep mining in hard rock mines. The microseismic events have no significant effect on the rock, so microseismic (small events) have no real effect on mine safety or mine production.”

As magnitude increases, the likelihood of damage to mine excavation increases. If there is rock mass damage caused by a seismic event, the event is termed a rockburst.

“Most rockburst damage in Ontario mines is minor, with no effect on mine safety or mine production. Rockbolts and surface support, such as steel screen, are put on the walls and roof of mine excavation. The rockbolts and screen generally prevent any rock from being displaced and causing workforce injuries, (see the photo).”

There are five Glencore mines in Ontario, Fraser Copper mine and Fraser Morgan mine are near Levack. Nickel Rim mine is beside the Sudbury airport. Kidd mine is 20 km north of Timmins.

Glencore is currently developing a new mine, Onaping Deep, near Levack.

“All five of these mines have elaborate seismic monitoring systems," Hudyma said. "Each mine would have between 20 and 100 seismic sensors located strategically in the mine, to give a precise location of each event recorded.

"Typically, event location accuracy is about 5 to 10 metres.

"Glencore also operates a series of strong ground motion sensors around their mines. These sensors are generally on surface and within 1 or 2 km of a mine. The intent of the strong ground motion sensors is to record very large events that may occur in a mine, typically greater than event magnitude +2.“

Large events and rockbursts have been recorded in Ontario for almost 100 years.

These large events are caused by a combination of three factors, high stresses due to depth, stiff and strong ground, and major geological features such as natural faults.

“Most deep mines have large events, and it is generally accepted that we cannot prevent the events from occurring. Because there are safety consequences related to large events, there are very elaborate risk management efforts underway to address safety issues," said Hudyma. "These risk management efforts include seismic monitoring.

"By monitoring events in mines, we get an understanding of what causes the events. This gives us an understanding of when and where the events are occurring.

"By knowing this, we can try to keep our workers away from where large events may occur. The rockbolts and support that are used in seismically active mines are designed to withstand most large seismic events; the bolts and quite specialized to prevent breakage from events.

“We have a good understanding of what causes most large events in mines. We have modified our mining practices to try to minimize the occurrence of large events and to keep our workers away from the large events.

"Changing mine excavation size, location, and shape is helpful. Good mine backfilling practices are helpful.

"Careful design of orebody extraction sequences and the design of mine pillars is helpful.

"In areas that we suspect may suffer large events, we use equipment to minimize the exposure of our workforce. Rockbolters that allow workers to be further away from the mine face are widely used. Tele-remote equipment such as scooptrams, allows us to keep workers away from potentially seismically active areas.”

There is a class of mining engineers called “ground control engineers”. These people are specialists in mining deep and challenging ground conditions.

“One of the primary tasks of ground control engineers is to try to understand seismicity in mines and to provide engineering design and operational guidance to alleviate events and keep workers in safe locations," Hudyma said. "Many state-of-the-art tools such as numerical stress modelling, ground displacement monitoring, and seismic monitoring are widely used to understand seismicity and rockbursting problems in mines.”

He said a great deal of effort is spent on training the workforce so that they have an understanding of seismicity and rockbursting.

“This allows them to work more safely in difficult ground conditions. And this is what the future holds. As the mines go deeper, the natural stresses increase and the number of mining-induced events and the size of these events is increasing.”

Exciting, if you are really interested Hudyma introduced an easy-to-use, citizen science seismographic computer device where earth movements can be monitored at home. Find out more about it by visiting this website. You can buy a kit for less than $150 and become a seismologist.

Another really neat map site is the Global Earthquake Monitor - which reports recent quakes worldwide or near you, just type in your location at this website. For example, Mar 31, 2022 02:08 GMT, Mar 30, 2022 10:08 pm (GMT -4) local time Lat / Lng: 46.54748 / -80.87452: Near Sudbury, Ontario, Canada.

This story went underground alright; the earth beneath us is moving we just don’t know it, another natural phenomenon on the back roads.