From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

Christmas traditions can often be very different between families, districts, countries, and cultures. These traditions have evolved over the decades and centuries, and looking back on what was considered important to communities can be an eye-opening blast from the past.

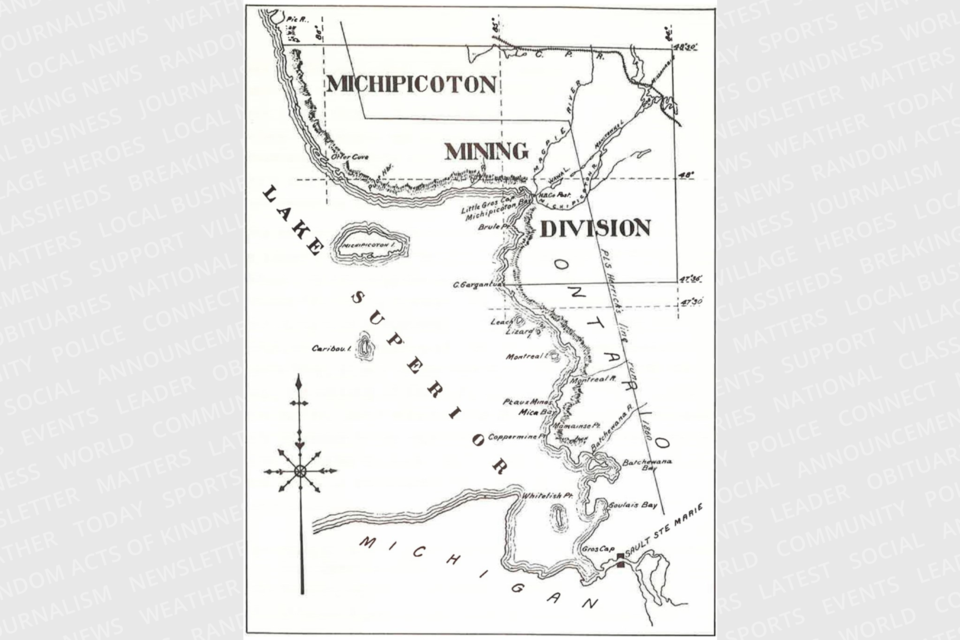

For the families of Michipicoten and the surrounding remote landscapes in 1900, Christmas was a time for gathering, drinking, dancing and shooting rifles.

In the winter weeks leading up to Christmas in 1900, holiday mail was delivered by dogsled teams. They travelled more than 60 miles between Michipicoten and Grassett in the northern Algoma wilderness.

Due to the far distances, the mailmen were often exhausted from the trek, as they were frequently forced to pull the sleds themselves when the dogs were overworked. Regardless, the parcels arrived at Michipicoten in time to be received for Christmas.

Crowds would always gather when postmaster M.J. Burke handed out the packages, with keen eyes hoping to catch a glimpse of what each parcel contained. Presents were then hidden from sight in houses until the community Christmas tree would be placed in the Ojibway schoolhouse on Christmas Eve morning where the holiday festivities were celebrated every year.

As a tradition, the tree was cut in the early hours of Dec. 24 and decorated in the schoolhouse hall where students could barely contain their excitement for Christmas.

Meanwhile, a group outside would prepare the rifle range for an annual competition. Marksmen from the surrounding Algoma district would celebrate Christmas by participating in a shooting challenge. A target would be placed 400 yards down the range, and the shooter with the highest score would win a turkey donated by Mr. Burke himself.

With evening turning to night, guests began arriving in Michipicoten from all corners of northern Algoma. Of particular note were the Norwalk miners, whose jingling bells and boisterous singing were beacons in the darkness as they serenaded owner Sam Moore for the mine’s success:

“Sammy lent a man his mill

And the man got the loan of Sammy’s mill,

‘Sammy’ said he, ‘will you lend me your mill’

‘I’ll lend you my mill,’ said Sammy”

Several nationalities were cherished guests at the school house on Christmas Eve, including Scottish, English, Irish, Finnish, and 'hard-bitten' Canadians along with Ojibway family and friends. Bottles of Christmas cheer were uncorked and tobacco smoke billowed and swirled as everyone drank toasts to one anther's fortunes. Bill Kimball acted as chairman of the festivities, as laughter and song filled the hours before Christmas.

When the clock struck midnight, Kimball vanished from the celebrations.

Minutes later, jingling bells announced the arrival of Santa Claus, dressed in a heavy fur coat and adorning a whiskered beard. The children were ecstatic to receive their presents at last. Most of the adults, however, rebelled against the pressure of their peers to unwrap their gifts for all to see, instead saving them to be opened at a more private, opportune time.

With Santa’s departure, Kimball returned to the hall and was asked to deliver a Christmas speech to the Michipicoten community:

“Fellows, I am not much on speech-making but as you all know our Lord and Saviour was born 1900 years ago. There’s not many of us here know much about him, but he was a very good fellow anyway, and it would not hurt us at all if we stopped now and then to remember it.”

Following Kimball’s speech, all of the chairs were pushed to the side and Joe Ball from the Norwalk Mine pulled out his fiddle. Everyone joined together on the dance floor and performed the quadrille. Similar to American square dancing with couples moving in rectangular formations, the quadrille was fashionable throughout the nineteenth century.

On Christmas Day afternoon, long after the dancing and rip-roar partying, the marksmen assembled at the rifle range.

Mr. Peter Arnott was selected as the judge or “marker” of the competition and wandered down range towards the target.

Normally, pits were dug out as safety measures to protect the judge from any stray bullets that may be accidentally fired from drunken foul play. However, due to either laziness or a lack of time, there were no pits on the Christmas of 1900. As a result, Mr. Arnott stood a considerable distance away from the target.

One by one, the marksmen got into position, aimed and fired at the target. Mr. Angus Gibson, manager of the Grace Mine, cemented himself as the early leader in the competition. However, the Norwalk Mine’s Joe Ball, who had a pristinely clean rifle and “accounted for more game than any other in the district”, soon claimed the new high score.

Prospectors from mines around Michipicoten and cabins scattered throughout the Algoma hinterlands continued taking turns shooting until the hat of marker Mr. Arnott suddenly flew off his head. The marksmen watched in horror as Mr. Arnott picked his hat up and poked his finger through the bullet hole punctured by the rifle ball. Rushing back up the rifle range towards the competitors, he asked “Who in the blazes fired that shot?”

Pointing at the offender, Jack Beith, Mr. Arnott snapped “You get the blazes out of here. You don’t know one end of a rifle from another!”

Whether the offender removed himself was not reported. However, Mr. Joe Legarde proved himself the greatest marksman that year, earning Mr. Burke’s turkey prize as a reward for his superior sharpshooting. With the rifle competition coming to a close, the Christmas festivities ended in Michipicoten for another year, before ringing in 1901.

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here