From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

In 1970, Heyden was the site of the Freedom Festival, a controversial rock and art celebration that divided the community.

The event was organized in collaboration with various community and anti-addiction organizations – the Alcoholism and Addiction Research Foundation, Sault Community Services Board, and the American Federation of Musicians, Local 276.

Notably, an organization known as the Bridge was also heavily involved; the organization functioned mainly as a drop-in centre for Sault Ste. Marie teens, but also handled drug and mental health crises. The organization advocated for sobriety and helped to provide activities and support for local youth.

The tentative plan was to hold the Bellevue Rock and Art festival in Bellevue Park. The event would take place over the course of three days, starting July 31, 1970.

Organizers hoped to bring in bands from across Canada and the USA, featuring rock and folk music, as wells as poets from across North America. Youth worked hard to fundraise for the events, and organizers saw it as an opportunity to get people “off their behinds” and working “in an environment which is conducive to discussion and to the testing out of their own ideas.”

As many as 10,000 people were anticipated to attend the festival, spread out over 3 days.

The festival was not without its critics and concerns. Bellevue Park, for example, did not have the facilities to handle a 10,000-person crowd, and portables would be costly. The festival would also have to receive special permission to allow people to stay in Bellevue overnight – and to receive an exemption to the anti-noise bylaw. Residents also objected to the park being monopolized during a summer weekend. Newspaper editorials lambasted the event organizers’ “surprising lack of foresight” in addressing these issues.

However, Mayor John Rhodes noted that the youth organizers were aware the concert might not be received well, wanted to give a good, well-organized impression, and were “handling it quite well.”

Ultimately, the organizing committee and city officials decided that Bellevue would not be the best location for the festival. However, according to organizers, “There’s no way it’s going to be stopped.” Other locations, including Pointe des Chenes and Strathclair Farm, were considered and rejected.

On July 20, just 11 days before the festival was set to begin, the Sault Daily Star announced that the event would be held at Heyden Speedway. Organizers renamed the event The Freedom Festival.

Festival organizers encouraged the public to keep an open mind, forget about media portrayals of Woodstock, which had been held the previous year, and remember that alcohol and drugs would not be available to attendees. They stressed the educational aspect of the event: “We were looking for a project the kids would be interested in doing, so they would have something to get involved in… The work involved in giving kids responsibility is part of the whole idea of the Bridge. Our whole trip is to let the kids run this place so they can learn.”

Youth weren’t just involved in organizing the event – they also worked in crews to clean the speedway before and after the festival.

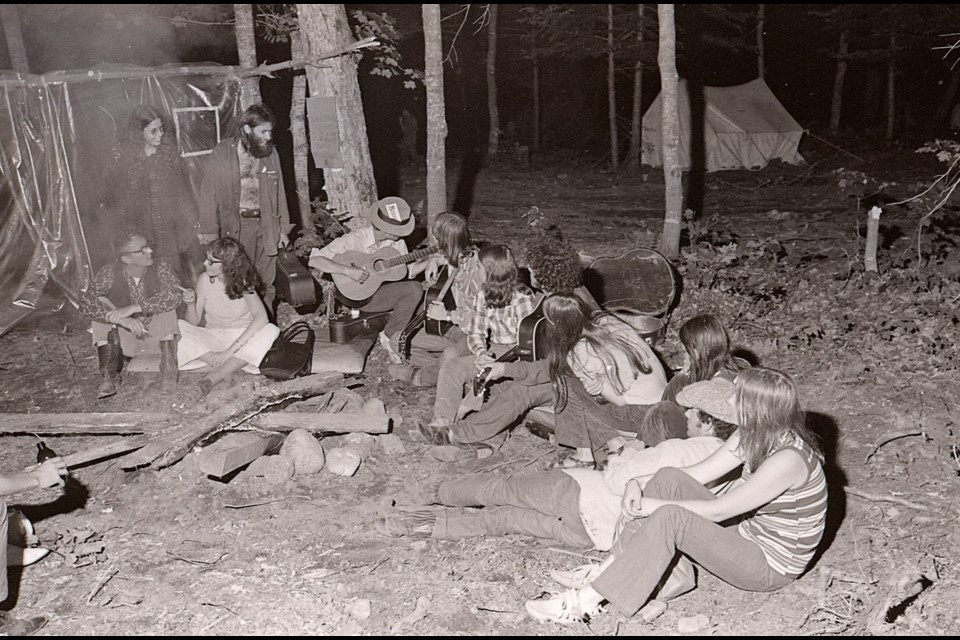

Friday, July 31, 1970, rolled around. People began to gather, with the festival starting around dinnertime and running until the small hours of the morning. Newspaper articles discussed the medical personnel on-site, the buses slated to transport people from the Sault to the speedway, the plentiful food for sale at the concession booths, and the numerous music groups that were slated to appear – nine local, seven from further afield. The Sault Daily Star ran photos of attendees socializing and playing guitar on the grounds, noting that there was “good music, good friendships, little or no trouble.”

Opening night saw some 1,500 people attend, about half of which spent the night on the grounds in a camping area referred to as “the village.” The following day was packed with events, running until 3 a.m. On Sunday, rain forced the festival to wrap up earlier than planned.

The owner of the Speedway donated uneaten food to the Bridge and the Camp Pauwating Youth Hostel.

As the festival ended, the Sault Daily Star reported, “hitch-hikers lined 17N all day Sunday. From the top of Pim Hill to [Goulais], every place a car might stop was alive with young people looking for rides.”

There was a tense moment on the Saturday when an attendee dove into a pond constructed on the property and hit his head on the bottom. He was pulled unconscious from the pond and had to be given artificial respiration… and after being revived, he had to be restrained to keep him from diving back into the water to “cool off.” He was taken to the hospital, but according to news articles, suffered nothing worse than a sore neck.

Over the course of the three-day festival, there were also approximately 18 drug cases that officials dealt with, including two cases of people taking strychnine capsules and needing to be transported to hospital. However, organizers described drug usage at the festival as “minimal and… quite under control.”

There were also reportedly “several knife fights,” but police said they did not result in any serious injuries. As well, some attendees complained of a motorcycle gang who “preyed on people, got drunk and made trouble.”

However, when local business owners were asked their opinion on the event, they reacted quite positively. A local hotel owner said he had no issues with guests from the festival, and noted that they all had money. A local restaurant owner echoed the sentiment, saying that she saw an increase in customers – and they were polite and with enough money to pay for a meal.

And the owner of Heyden Speedway spoke glowingly of the event: “I’d gladly give it to them another year. They are wonderful people and the property is a lot cleaner than when they came.”

The Sault Daily Star published a similarly positive editorial, highlighting that “not only was there none of the unruliness and lawlessness which some people had felt might be inspired by the rock festival, there was behaviour of a kind that had festival organizers and police and people in the area praising the young people for their manners and courtesy.”

Not everyone felt so pleased with the event. A handful of letters to the editor expressed concern for the festival, calling it “a sad commentary on the morality of a community and a social system.” One letter criticized the sight of young attendees drinking, smoking marijuana, and “partaking of ‘free-love’ acts.” The writer went on to label some of the attendees “’kooks’ or ‘freaks’ who only came to see how far they could go without reaction from authorities.” Other letter-writers fired back in defence of the festival, arguing that “free love” and drugs could be found numerous places.

Organizers were also very happy with how the festival went, citing the high numbers – as many as 15,000 over three days – and the diverse clientele from across North America. While there were some issues with the sound system, and while the rainy weather made the arts display difficult to present without damaging people’s works, the response was largely positive. They hoped to make the event a yearly affair, but some were concerned about the amount of work it would entail.

Regardless, organizers were delighted with the cooperation and opportunity for connections the festival afforded. As the director of the Bridge said, “If nothing more was accomplished, one more bridge was built between people.”

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here