From the archives of the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library:

Gliding in a canoe on the majestic waters of Lake Superior can be one of the most serene, summer pleasures to experience.

Slightly contoured, glass-like water that surrounds the canoe brings tranquillity and a sense of adventure! If the weather decides to turn, then the experience can become eerie and terrifying!

Greyish, heavy clouds start to roll in and the surrounding waters appear angry and dark, even black, and the canoeist is at the mercy of an extremely powerful force.

While attempting to navigate the unpredictable waters, both of these scenarios were common to the voyageur who, throughout the Fur Trade, navigated the Great Lakes with skill like no other!

The voyageurs, deemed the “engines of the fur trade”, ruled the trading waters during the seventeenth, eighteenth and early nineteenth centuries while the Fur Trade was booming. Beaver, otter, fox, lynx, muskrat, wolf and bear pelts were wanted for fashion.

Furs were in high demand in Europe and Asia. The voyageurs learned every corner of the greatest lake and became known for their skill of navigating Lake Superior and the other great lakes.

Many of the names we know today of inlets and coves were given by voyageurs. Sinclair Cove, Old Woman Bay and Pancake Bay to name just a few.

Most of the voyageurs who travelled Lake Superior came from the French-Canadian settlements along the lower St. Lawrence, often from the small farms and villages in Quebec. It was customary for the position of voyageur to be handed down from generation to generation and was considered a job to be proud of!

To become a voyageur was considered a privilege and their pride of profession was a prominent characteristic that each held!

A young man would have to make arrangements for wages and other specifics of his employment with an agent of one of the trading companies, such as the Northwest Company, The Hudson’s Bay Company and The American Trading Company, who were all involved in the fur trade. The young voyageur would then be ready to begin his career on one of the huge canoes that travelled the big waters.

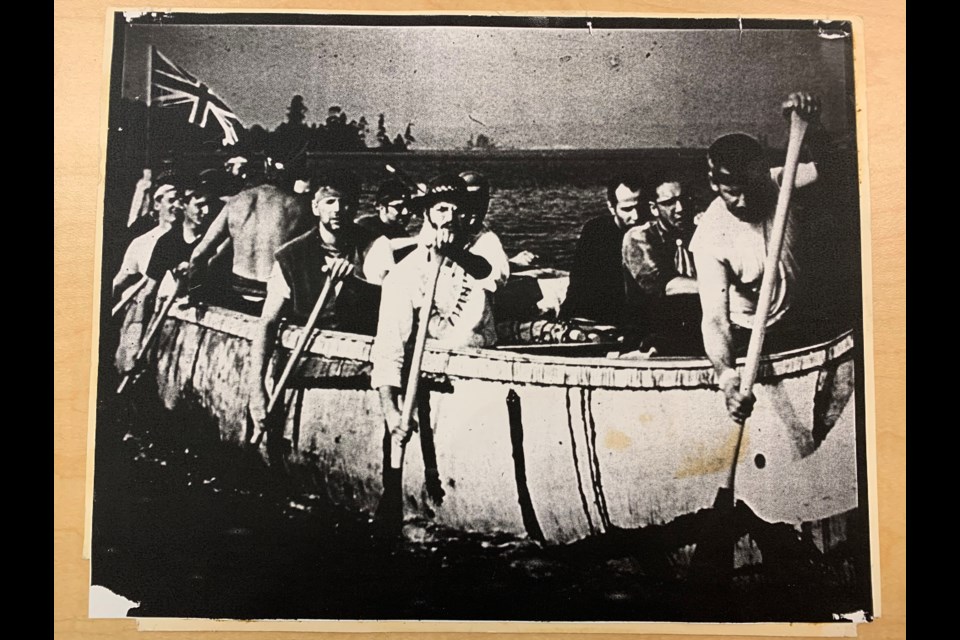

The canoes were primarily constructed of birch bark measuring 36-40 ft. in length. Their purpose was to handle the Great Lakes in any kind of weather and deliver the goods!

It took several men to lift the canoe when a portage was necessary. Not only was the huge canoe transportation during the day but it was a refuge for sleeping during an overnight stay onshore. An overturned canoe provided the necessary shelter from the elements for the voyageurs.

A voyageur was not a man of large stature but instead was on average about 5, 5” tall and strong, as the voyages called for great physical stamina.

A man with a smaller physical build was ideal as this would allow for ample room in the large canoe to transport the massive amount of cargo. As a result of all of the paddling required, the voyageurs typically had overdeveloped chests and arms but smaller legs.

When portaging was required, they carried huge loads while quickly navigating by foot over rocky trails and thick bush.

Usually, about 12 men travelled in a canoe that could transport up to seventy, 90-pound cargo packs.

Carrying two of these packs on a portage was not uncommon. Due to the heavy strain placed on their bodies, it also wasn’t uncommon for a voyageur to suffer a heart attack or a strangulated hernia.

An 18-hour day was the norm for these men who would paddle up to 45 strokes per minute.

Intrigued with the voyageurs, in 1820 Thomas McKenney, an official for the United States Bureau of Indian Affairs, estimated that their daily paddle strokes were approximately 57,600. He recorded that a canoe of voyageurs could lift their canoe out of the water, fix any issues, reload it, cook breakfast, shave, wash, eat and re-embark in 57 minutes!

Throughout the summer and winter, their manner of dress was quite distinct.

They typically wore a red woollen cap, a pair of deerskin leggings that reached up just past the knees, held up by a string attached to the belt around his waist and a pair of deerskin moccasins with stockings on his feet. The thighs of his pants were left bare.

He often sported a pipe and a colourful sash with a pouch that hung from it. He also donned a hooded cloak called a capote.

Many people of today know traditional songs of the Voyageur without realizing what history they hold.

Alouette Gentille Alouette, was a well-known song, sung by the voyageurs as their paddles eagerly dipped in and out of the cold waters of Lake Superior.

Voyageurs chose and wrote songs for numerous reasons. He wrote and sang for pure enjoyment, he sang to help keep the rhythm of paddling and he sang to help break the monotony of the day, paddling anywhere from 15 to 18 hours.

The steersman chose the song and the pitch, setting the stage for the others to join in. To hear a canoe of voyageurs in the distance must have been quite impressive as they propelled themselves forward with repeated, intentional strokes towards the next trading post or shelter for the night.

They sang in French about everything that each could identify. They sang of their loves, their romances, their country, humorous jingles, poetry, obscene versifications and of course they sang of their canoe!

Proud, sturdy, resilient and full of life, the voyageurs intentionally portrayed their quality of character by decking themselves and their canoes in colour. A red feather on the top of their hats and one on each end of their canoe indicated that their vessel was tried and found worthy!

The frail construction of these giant canoes was contradictory to the type of man needed to navigate them. These canoes tested a man’s ability to push his limits physically and mentally.

Being made primarily of birch bark, the paddlers were forced to keep their lower bodies still while their upper bodies did the work of driving the boat forward. With feet positioned on the floor of the boat, the canoe men were careful not to break the gum on the seams of the canoe. Its delicate construction also made getting in and out tricky.

So as not to disturb the interior floor, voyageurs became skilled at swiftly springing themselves out of their canoe and into the chilly waters, immediately after their last paddle dipped the water.

Never was a canoe launched up onto a sandy or rocky shore but was first anchored offshore. When transporting passengers, a voyageur had no reservations about lifting passengers out and giving a piggy-back ride to shore! Whether male or female all were similarly transported.

Once everyone was out of the canoe, it was gently escorted to shore where it anticipated its next day’s voyage.

Faintly as tolls the evening chimes

Our voices keep tune and our oars keep time.

Soon as the woods on shore look dim,

We’ll sing at St. Ann’s our parting hymn,

Row, brothers row, the stream runs fast,

The rapids are near and the daylight’s past.

Written in 1804 by Thomas Moore, voyageurs adapted his verse to song on a trip from Kingston to Montreal.

Each week, the Sault Ste. Marie Public Library and its Archives provides SooToday readers with a glimpse of the city’s past.

Find out more of what the Public Library has to offer at www.ssmpl.ca and look for more Remember This? columns here